Six years later, more evidence shows the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act benefits U.S. business owners and executives, not average workers

Shutterstock

When policymakers were debating the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017,

many proponents claimed that average U.S. workers would benefit via wage increases. These adherents of trickle-down economic theory argued that, alongside other business tax cuts in the law, slashing the C-corporation tax rate by 14 percentage points, from 35 percent to 21 percent, would reduce these firms’ cost of capital—or how expensive, after tax, it is to invest in new projects. This, proponents said, would spur private investment, which, in turn, would boost workers’ productivity and thus increase wages and job openings.

This highly speculative string of contingencies is a tenet of faith among supply-side economists. Yet the

empirical evidence has never been on their side. And now, nearly 6 years after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was signed into law by former President Donald Trump,

a new study further reinforces that these business tax cuts benefit highly paid executives, not the vast majority of U.S. workers.

Indeed, the paper—by Patrick Kennedy, Paul Landefeld, and Jacob Mortenson, all of the U.S. Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, and Christine Dobridge of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors—

finds that almost all of the benefits of the 2017 law’s signature $1.3 trillion C-corporation tax cut went to high-income shareholders and executives—not low- or moderate-income workers. (This $1.3 trillion figure refers to the 10-year cost estimate specifically for the C-corporation rate cut provision, provided by the Joint Committee on Taxation before the bill was passed.)

Using anonymized tax records and sophisticated methods, the four co-authors

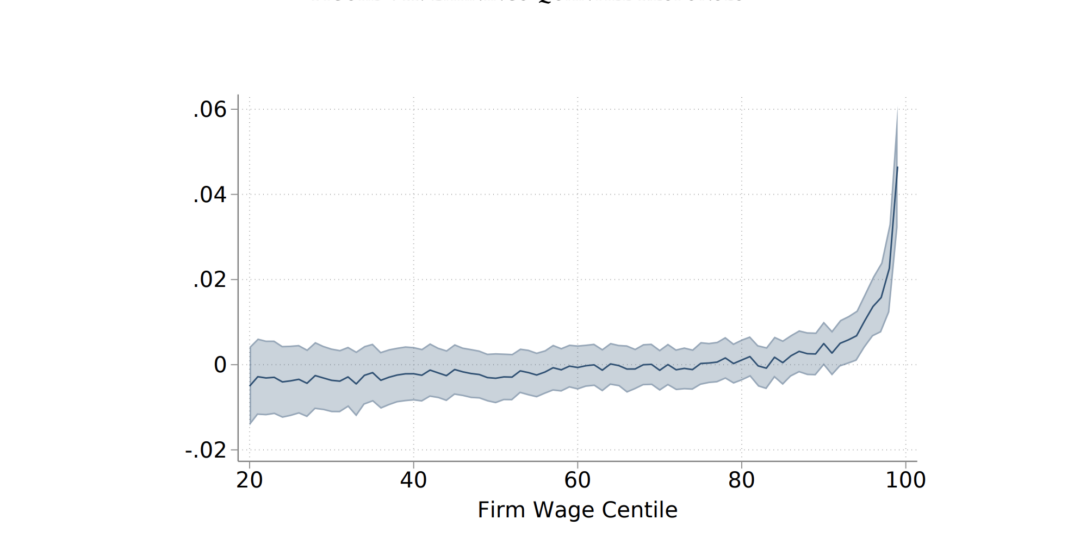

find that workers below the 90th percentile in their firm’s earnings distribution did not receive any wage boost from the C-corporation tax cut. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Only already very well-paid workers saw a wage increase from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017’s C-corporation tax cut

Change in annual earnings for U.S. workers at various within-firm income positions between those working at C-corporations and those working at similarly situated S-corporations

NOTES: Unit of analysis is firm year. The bottom 20 percent of the distribution is excluded because the presence of part-time workers makes the estimate imprecise. Standard errors are clustered by firm and error bands show 95 percent confidence intervals.

SOURCE: Patrick Kennedy and others, “The Efficiency-Equity Tradeoff of the Corporate Income Tax: Evidence from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Working Paper (2023), available at https://patrick-kennedy.github.io/files/TCJA_KDLM_2023.pdf.

To reach these conclusions, Kennedy and his co-authors compare C-corporations—the legal structure used by U.S. firms, including all public companies, seeking large amounts of outside investment—with similarly situated S-corporations, which raise money from a limited number of shareholders and are treated as a pass-through entity by the U.S. tax code. S-corporations’ profits are not taxed at the firm level but instead flow to owners and are taxed at the individual level. C-corporations received a larger tax cut in 2017 than S-corporations did, a difference the authors exploit for their analysis.

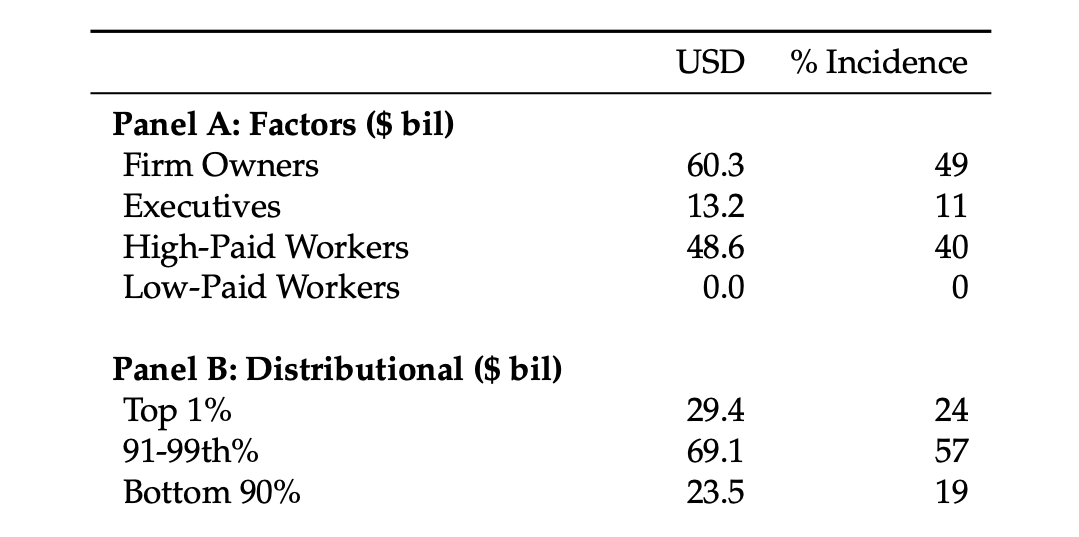

Kennedy and his co-authors conclude that 49 percent of the gains from the C-corporation cut went to the owners of firms, while 11 percent went to firm executives (the top five highest-paid workers at the firm). The other 40 percent went to high-income workers (or those above the 90th percentile within their firm). Precisely zero percent went to low-paid workers (or those below the 90th percentile). This means executives alone pocketed $13.2 billion annually—a pay bump of roughly $50,000 per executive—while median workers received nothing.

In total, 81 percent of the gains from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s C-corporation rate cut were captured by the top 10 percent of the U.S. income distribution, with the top 1 percent seeing a whopping 24 percent of the benefits. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The top 10 percent of the U.S. income distribution captured more than 80 percent of the 2017 corporate tax cut benefits

Annual change for U.S. workers by job role and income as a result of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s C-corporation tax cut

NOTE: To compute distributional incidence, gains of firm owners are allocated to workers using data on capital ownership from the Federal Reserve Distributional Financial Accounts.

NOTE: The top 10 percent of the income distribution does not receive 100 percent of the benefits because some high-income workers, while in the top 10 percent of earners at their firms, are not in the top 10 percent of the country’s total income distribution. Likewise, some low-income workers are also business owners, usually in the form of mutual funds held in retirement accounts.

SOURCE: Patrick Kennedy and others, “The Efficiency-Equity Tradeoff of the Corporate Income Tax: Evidence from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Working Paper (2023), available at https://patrick-kennedy.github.io/files/TCJA_KDLM_2023.pdf

The paper does not address other types of inequality, but those at the top of the U.S. earnings distribution are disproportionately

White or Asian, so it is likely that the distributional impacts on display in this study represent an exacerbation of

racial income gaps in the United States.

Further, the four co-authors find that the C-corporation rate cut delivered $122 billion in additional private income per year—but to achieve that modest output gain, the federal government spent $86 billion in foregone revenue. It’s important to note that this figure is lower than what the

Joint Committee on Taxation and

other scorers have estimated because this paper’s authors find that the tax cut spurred some additional profits, leading to slightly higher taxes paid than had there been no feedback effects.

One caveat to keep in mind: This study is probably most illustrative of the impact of the C-corporation cut on mid-sized firms, since there are few S-corporations large enough to serve as a reliable comparison group to large multinational C-corporations. Additionally, to target the analysis on firms that the authors are confident received a large tax cut, the sample is restricted to companies with at least 50 employees and $1 million in sales per year from 2013 to 2016.

The findings from Kennedy and his co-authors dovetail with analysis of

pre-Tax Cuts and Jobs Act tax breaks from Eric Ohrn from Grinnell College. Ohrn finds that executive pay increases by 25 cents for every dollar of tax cuts received. Ohrn also finds that a 1 percentage point decrease in effective tax rates increases the compensation of the five highest-paid executives at affected firms by 4.2 percent, or $611,000 on average. This is very similar to a

previous finding from Kennedy’s three co-authors, who, using a different dataset, traced the impact of the same business tax cut to determine that corporate officers received a 4.4 percent increase in compensation for every 1 percentage point decrease in the tax rate, compared to a more modest 1.3 percent raise for nonofficers.

Why do owners and executives capture most of the benefits from business tax breaks? The best explanation is that U.S. labor market inefficiencies prevent workers from being rewarded for their productivity. Low- and moderate-income workers lack the necessary bargaining power to demand their fair share of tax cut proceeds, while executives enjoy undue influence over their compensation, winning raises that are not justified by firm performance.

This is consistent with research on

monopsony, in which employers enjoy the market power necessary to keep wages inefficiently low. Indeed, the

previous study from Kennedy’s three co-authors finds that smaller firms are more likely to share tax break proceeds with median-wage workers—evidence that market power, proxied here by company size, plays a role.

Additionally, Ohrn finds that firms with large institutional shareholders and shorter executive tenures—examples of strong corporate governance structures—did not increase executive compensation with proceeds from their tax breaks. This implies that companies with less robust checks on corporate governance may be falling prey to “executive capture,” in which CEOs leverage relationships with members of their Boards of Directors to win higher compensation.

This theory is corroborated by other researchers who have looked specifically at Congress’ past attempts to use the tax code to limit executive compensation. Section 162(m) of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, for example, removed the tax deductibility of CEO pay. While a similar provision in the law that applied to nonprofit organizations did

appear to reduce CEO salaries, Section 162(m) had little to no effect, according to

multiple rigorous studies. This implies that even when policymakers effectively make it more expensive to pay CEOs, executive salaries still rise—proof that these exorbitant pay packages are not the result of rational economic decision-making.

The new findings from Kennedy and his co-authors are important for two main reasons. First, they provide important nuance to an age-old policy question: Who bears the costs or benefits from business tax changes? Historically, researchers have delivered fairly crude, aggregate estimates. The Joint Committee on Taxation

assumes, for example, that based on its synthesis of the academic literature a full 100 percent of the cost of tax increases is borne by owners in the short run, and 75 percent is borne by owners in the long run, with workers paying the remaining 25 percent. The committee increases the share borne by owners to 95 percent for tax changes affecting pass-through businesses because they have less ability to move capital or operations abroad to avoid taxes.

In contrast, the Congressional Budget Office

allocates 75 percent to capital income and 25 percent to labor income. The U.S. Treasury Department takes a more

complicated approach that distinguishes between normal and supernormal returns to capital, but the upshot is an 82 percent-18 percent split between the capital and labor incidence of the corporate tax.

Yet the Joint Committee on Taxation, Congressional Budget Office, and Treasury Department all assume that the benefits or costs to workers from tax changes mirror the distribution of wages more generally. The evidence above belies that assumption, demonstrating that wage increases from tax cuts are even less equally shared than the nation’s

already very unequal wage distribution. This means that researchers and policymakers must think more granularly about the heterogeneous effects of tax policy.

Second, the authors’ findings show how taxes interact with other economic phenomena, such as market power. Given the outsized power of employers in the U.S. labor market, corporations may be able to both hoard the proceeds of tax cuts and pass on the cost of tax increases to workers. This asymmetrical situation would leave policymakers in a bind: Reversing tax cuts alone might not be enough to claw back the unjustified gains that shareholders and executives received from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

That’s why researchers and policymakers must think about combating inequality more holistically. Tax policy researchers, for example, should adjust their models’ assumption that labor markets function competitively. And policymakers should consider tax policy changes in concert with other reforms that address inequality in the United States, such as

lax corporate governance standards and weak

labor and

antitrust protections.